Text adapted from: "The adult patient with a posttraumatic stress disorder," in Psychiatry in primary care by Francesca L. Schiavone and Ruth A. Lanius (CAMH, 2019).

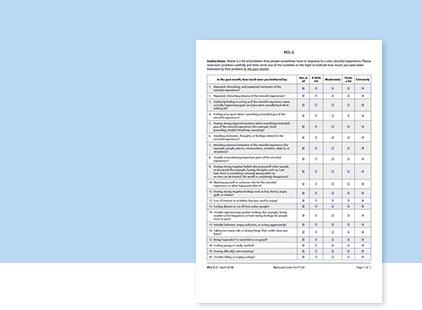

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-5)

The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-5) is a 20-item self-report tool that corresponds to the 20 symptoms listed in DSM-5 (Blevins et al., 2015). It can provide a global assessment of PTSD severity both at the time of diagnosis and over the course of treatment.

Self-report tool that assesses PTSD severity at the time of diagnosis and over the course of treatment.

Print Version

On a 4-point scale, scores can be tabulated for individual items to give information about the severity of the four DSM-5 symptom clusters. If a score of 2 (moderate) is considered to be a positive endorsement of a given criterion, the PCL-5 can be used in combination with a clinical interview to make a provisional DSM-5 diagnosis. Testing the PCL-5 with veterans has determined a score of 31 to 33 to be a valid cutoff for a positive screen, but more work is necessary to validate this score in civilian populations (Bovin et al., 2016).

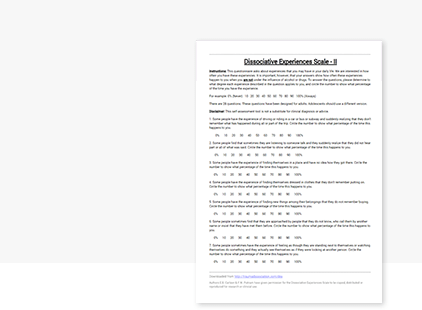

Dissociative Experiences Scale

Because the DSM-5 incorporates a dissociative subtype of PTSD, it is useful to screen for dissociative symptoms, which are not captured by the PCL-5.

The self-report Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES) asks respondents to rate what percentage of the time they experience a given dissociative symptom (Bernstein & Putnam, 1986). The general population average is 4 to 8 percent compared with 26 to 42 percent among people with PTSD (Carlson & Putnam, 1993). The DES cannot be used for diagnosis, but scoring over 20 per cent indicates the need to further explore dissociative symptoms (Lanius et al., 2016).

Clinical Presentation

The first diagnostic criterion for PTSD is having experienced a traumatic event, which DSM-5 defines as “exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence” (APA, 2013). The person must experience symptoms across four clusters: intrusions, avoidance, negative alterations in mood or cognition, and alterations in arousal. Symptoms must be present for more than one month and result in significant distress or impairment. (See Diagnosis for full DSM-5 diagnostic criteria.)

In DSM-5, PTSD is no longer classified as an anxiety disorder. It has been moved into a new category called “trauma and stressor-related disorders.” This separate classification acknowledges that not all people with PTSD have a presenting complaint related to anxiety. PTSD may also present as profound dysphoria and anhedonia, significant irritability and behavioural reactivity, or persistent dissociation and detachment.

Other common presentations include low mood, anxiety and panic, specific phobias, anger problems, insomnia or nightmares, interpersonal difficulties, occupational dysfunction and emotional numbness. The person may experience prominent feelings of guilt and shame, and a sense of “moral injury.” In military populations, guilt and shame are associated with later development of PTSD (Nazarov et al., 2015).

PTSD may also present as somatic symptoms and frequent use of the medical system. A study of primary care patients who met criteria for PTSD found poorer overall health functioning and higher rates of using health care services (Gillock et al., 2005).

Complex Trauma

The heterogeneity in the clinical presentation of PTSD can be partly explained by significant differences in the types, patterns and timing of traumatic events. The impact of a single event in adulthood is different from the impact of repeated childhood sexual or physical victimization or neglect by a primary caregiver. Because the latter occurs repeatedly during critical developmental periods, it interrupts or prevents normal developmental tasks such as consolidating identity, forming basic trust in others and learning affect regulation skills (Glaser, 2000; Herman, 1997).

People with such complex traumatization are more likely to present with dissociative symptoms, somatization, extensive comorbidity, intense suicidality, and alterations in identity and interpersonal relatedness. People with a history of complex trauma are more likely to develop symptoms after subsequent adulthood trauma (Herman, 1997; Lanius et al., 2016).

Dissociation

Many of the symptoms captured in the core diagnostic criteria for PTSD represent hyperarousal symptoms, or under-modulation of the central nervous system in response to trauma-related cues. However, 15 to 30 percent of people with PTSD, particularly those with chronic childhood traumatization, have over-modulated traumatic emotions and responses, manifested as dissociative symptoms (Lanius et al., 2016).

Dissociation is “a disruption of the usually integrated functions of consciousness, memory, identity, or awareness of body, self, or environment” (APA, 2013). This definition encompasses the depersonalization and derealization symptoms identified in the PTSD dissociative subtype (feeling detached from the self or environment).

Dissociation can also include memory impairment, particularly loss of memory of traumatic events; reduced response to the environment (physical and emotional numbness); spontaneous “trancing” or “spacing out”; and identity confusion or fragmentation (Lanius et al., 2016).

In PTSD